The Media Development Investment Fund (MDIF) invests in independent media, aiding the free flow of news, information and debate that people need to build thriving societies. MDIF applies these principles in their management of the investment vehicle Pluralis, which caught our attention recently as they’ve now added impact bonds to an already diverse blend of funding.

“If you’re financially viable, you can be editorially independent. And if you’re editorially independent, you can have an impact on your society.”

This was how Patrice Schneider, MDIF’s Chief Strategy Officer, summed up the organisation’s theory of change at the International Journalism Festival. We began our conversation with the origins of this idea.

How did you first encounter the idea that financial viability enables editorial independence? Has it been with you for a long time in your career?

It's the first time anyone has asked me this in 22 years. And the answer is yes. I was one of the first Reporters sans frontières (Reporters Without Borders). This organisation’s founding idea, 30 years ago, was to send reporters to places where there was no coverage. My first beat was covering the Afghan refugees during the first Afghan war, under Soviet occupation.

A young student, I went to Reporters sans frontières with my pitch, and they said, ‘Fine, brilliant idea, but we have no money.’ So, I borrowed money from fellow students and my family, and I paid it back. Self-financing: that was something that really stuck with me.

This can be very ethically complex territory in the world of journalism. I had a colleague who worked as a paparazzo, and he did it not because he had a sincere desire to cover celebrities for the tabloids, but because he was using the money to fund his coverage of the atrocities of the Algerian civil war in the 90s, fought between the Algerian government and various Islamist rebel groups from 26 December 1991 – nobody wanted to pay for that, but he knew he had to go there and bring this news to the world.

In French publishing, typically they put a directeur general in charge of the business and, on the other side, they have an editor-in-chief; the idea is that these two will fight it out and constructive chaos will bring something positive. When I arrived, as a French-Canadian in a French corporate environment, I went to them and I said, ‘No, I want both.’

Flash forward quite a few years, I meet MDIF. And I said, ‘Wow, this is this is exactly the combination I want.’ I think the beauty of the craft is that one really can be at the centre of both – business and editorial – which is why I enjoy my job so much.

What is media capture and what’s the state of it in 2023?

The global political landscape has witnessed the rise of illiberal democracy and populist autocracy in recent years, which has become significant for Americans and Europeans. Europe, being the epicentre of this phenomenon, has seen countries such as Hungary, Poland and Slovakia become key theatres in this transformation.

At the heart of the illiberal democracy model lies media capture. Media capture refers to the process through which powerful individuals, groups or governments exert influence over media outlets, via ownership takeovers, to shape the narrative and control the flow of information. Media outlets are co-opted, silenced or subjected to heavy government influence, resulting in a lack of diverse perspectives and the spread of propaganda. This undermines the democratic process by limiting the access to independent information and fostering an environment of misinformation and disinformation. Media capture has even played a significant role in the Ukraine conflict by fuelling the spread of propaganda, misinformation and fake news, contributing to the polarisation and escalation of tensions in the region.

Plūrālis, a unique coalition of stakeholders from Western Europe, including MDIF, has recognised the existential threat posed by this model in Eastern Europe and has rallied to address this challenge. One of the ways we do that is by stopping media capture.

What are the funding goals for Pluralis? How has Pluralis used that funding to stop media capture?

The vision is €100 million. We're now at €50, halfway.

The long-term goal – an obsession, really, because this is a big problem in our society – is preventing the collapse of discourse in the public sphere. Keeping that independent spirit is a much bigger problem than the €100 million will solve. There’s discussion of Pluralis being a pilot project for solving this greater problem, but ultimately the €100 million will go to very concrete and symbolic preventions of capture.

With the €50 million the fund has raised so far, we've stopped capture in three places, each with a different flavour.

The first is Slovakia. The most independent newspaper in Slovakia, historically profitable, was at one point sold to a toxic investment group, who tried to control the narrative because they were linked to the government. So, we bought them out, we literally bought their shares, which until we stepped in were more than 50%. This is decapture – the goal is for Pluralis to maintain plurality in Slovakia, not to fight the investment group or even the government. Our intervention ensures that there is another voice saying something different.

Example number two is a typical media capture prevention. Rzeczpospolita is “The Wall Street Journal of Poland” – so, a big target. It was going to be bought by a state-owned gas company called Orlen. We got wind of that by pure chance; we bid against Orlen, they were going to pay a higher price, but we managed to win anyway.

The first two examples are legacy media, but for a third flavour, take the example of a news website in the Western Balkans: very reputable, and with an outsize effect on their society because of the stories they break. I can’t fully announce it yet, but I can tell you the reason why we’re preventing the capture in this third case. They’re important to the media ecosystem; they break stories no one else will and force larger outlets to cover them. That’s how they earn the interest and support of Pluralis.

Why is blended funding an effective approach for strengthening independent media?

Blended funding allows us to broaden to more actors in civil society who say this is important. And if you've built an entity that has blended ownership, governance and funding, no single entity controls it. This approach deals directly with an increasingly important question, which is, ‘Who owns the media?’

Impact investment allowed our blended funding to happen. I don't think it would have been possible without it, because some organisations don’t want to be limited to grants; they say, ‘No, I want an investment.’ We also have high-net-worth individuals coming in, wanting to make this a part of their impact investment portfolio. And finally, most recently, we have the case of banks, like GLS.

Can you describe the added value of the GLS Bank partnership and impact bonds for Pluralis?

The partnership with GLS allows us to reach out to 300,000 retail clients. These people are actually getting involved and saying, ‘I’m only going to get a small return on investment on my impact bond, but I’m participating in something important. Independent media.’

There's a bigger message here, which is to say, it's not just the job of foundations and independent media companies to take care of public discourse. It’s all of us.

I recently spoke at the general assembly of all the small shareholders of GLS. They're bringing in €5 million (of our €100 million goal). But I told the Pluralis board that the €5 million is not the important part. The important part is, people in the street saying, ‘Hey, I'm going to buy a bond for independent media, because free flow of information is something essential for the common good.’

These are not rich people. They just care.

How does MDIF measure the social impact of clients?

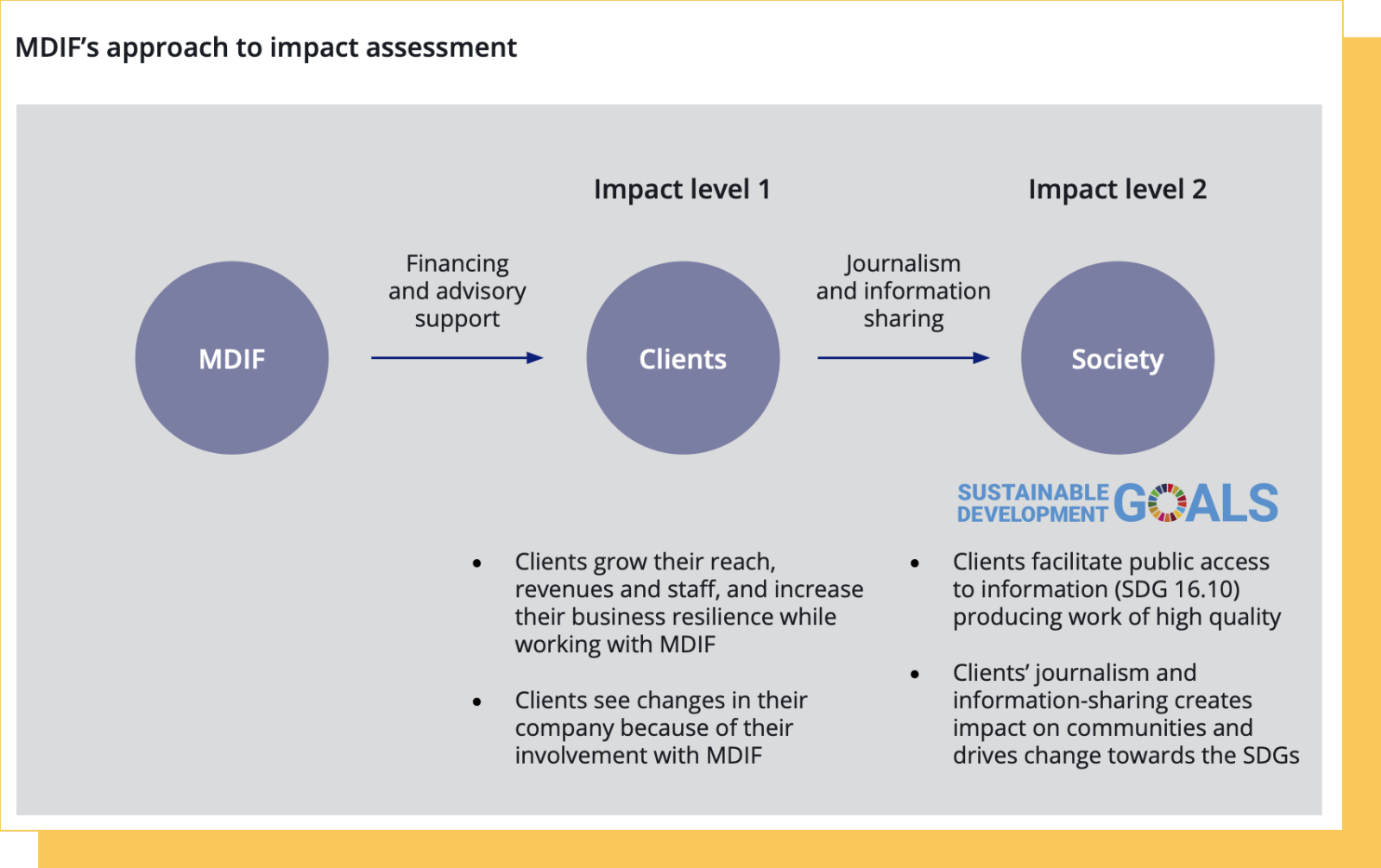

According to our theory of change, if you are financially independent, you will be editorially independent, and have a positive impact on society. To get at this, we measure how we make you, as an independent media outlet, more financially viable: sales, reach and financial viability. That’s the first level.

The second level of our impact is about the impact you have on society. This is a very subjective subject, so we've chosen very focused areas: accountability, corruption and elections. Could we measure other ways, including gender or human rights? Absolutely. And the clients who address these themes measure for them. But we decided to remain very focused for our own dashboard, which we’ve been perfecting over the course of 12 years now (see image).

Do clients view themselves as social impact actors, aligned with particular SDGs, or is this more of MDIF’s perspective?

They're the consummate social entrepreneurs! I don't think they consider themselves that way, but I certainly do, because they are constantly balancing profit and society.

If you’re truly independent, you’re always measuring your financial profit and weighing decisions against that, asking questions like, ‘Will covering this subject cost me something on my bottom line?’ The media outlets that are really independent have been like that for 400 years.

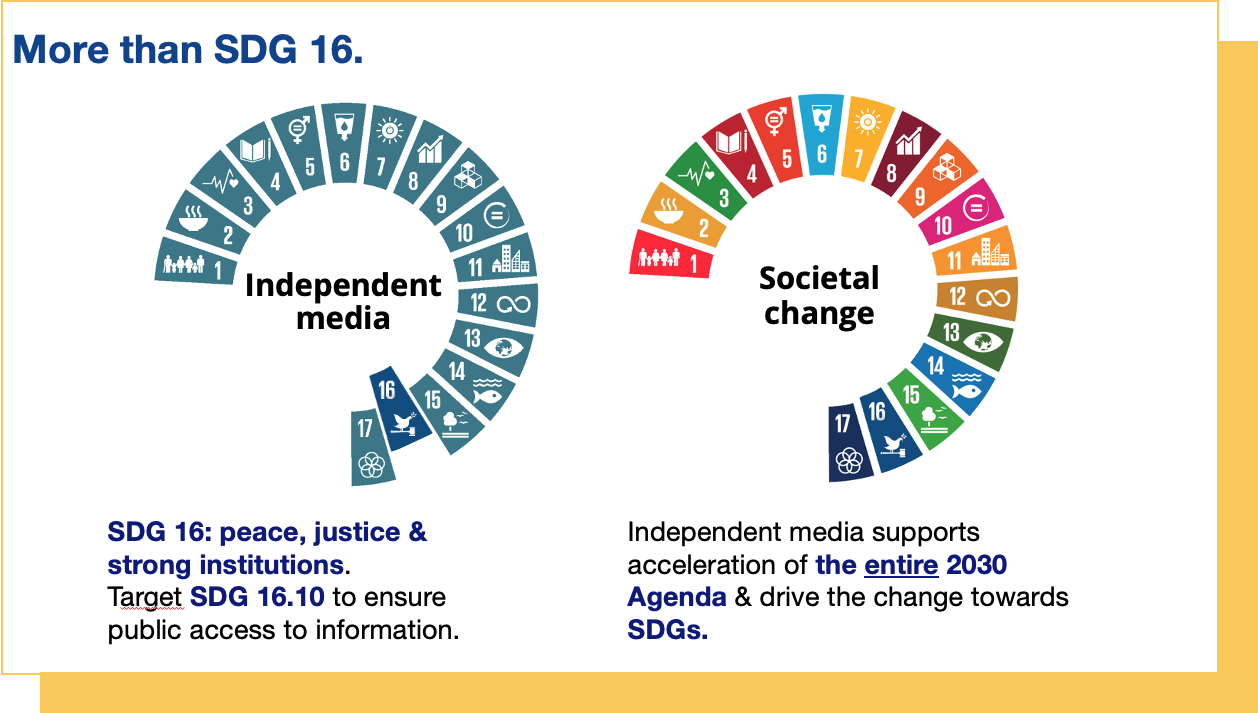

If you look at SDGs, our work is in 16: peace, justice and strong institutions. Track 10 of SDG 16 is access to information that society needs. 16.10 is a very narrow part of the SDGs, but our argument is that the work of our clients actually crosses the whole board. If you don't have a free flow of quality information, you can't have, say, water management that is properly geared towards society. You can't have gender inclusion, you can't have climate action – it's really a transversal thing.

How is independent media faring in Ukraine right now? Do you have a wish list for rebuilding Ukraine’s media ecosystem when the war ends?

We still have four clients in Ukraine, but now the investment logic has been put on hibernation, because there's no use trying to get a return on investment, even an impact return, during the war.

But we don't let go – that’s part of MDIF’s DNA. We don’t give grants usually, but in this case, we are raising grant money so that we can keep these organisations alive for the future.

Some Ukrainian clients have an interesting perspective on this. I spoke with one of our Ukrainian publishers and he said, ‘Well, thank you for the grant, but if you give us a loan, it means that you believe in our future.’

That was a very powerful answer. We gave him a grant, but it just shows you sometimes that there's a message behind the impact investment – of hope. We do believe in that future.

Ukraine is going to have to rebuild their infrastructure. If you’re starting on that process, it’s important to think about plurality of media. It’s not just about roads, hospitals, education, which are all so needed. It's also about rebuilding a plurality of voices. I think there's a huge opportunity in Ukraine to do that. I believe that impact investment can be a large part of the solution.